Barriers to Critical Thinking

To think critically, we must clear away not just distractions around us but distractions within us. Much of our moment-to-moment thinking is mechanical instead of critical, and when an issue affects us personally, our thinking tends to be emotional.

Breaking Through Mechanical Thinking

Mechanical thinking is automatic and pre-programmed, meeting a given stimulus with a given response. You can recognize mechanical thinking because it shuts down possibilities and thereby prevents critical thinking.

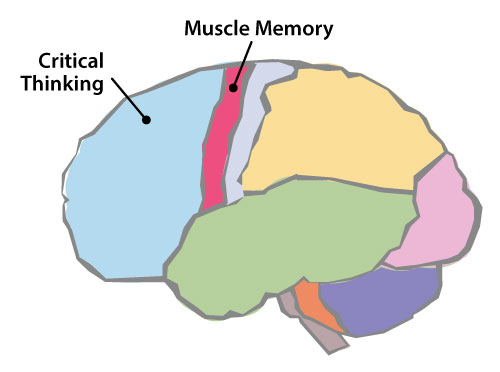

In that way, mechanical thinking is similar to muscle memory—you can walk, eat, and even drive without a great deal of conscious effort. That's because you've done these tasks so many times, your brain has stored them in a band of neurons attuned to routine action. If you use those same neurons when you ought to be using your prefrontal cortex, mechanical thinking takes the place of critical thinking.

When you notice a thought that shuts down possibility, answer it with a question that opens up possibility:

Don't Say |

Do Say |

|

|

Managing Emotional Thinking

Emotional thinking occurs when our feelings lead our thoughts rather than the opposite. Often we have an emotional response to a stimulus—I love that idea or I can't stand that suggestion—and then someone challenges us: "Why?" We scramble to find reasons to justify our emotions.

Manage Emotional Thinking

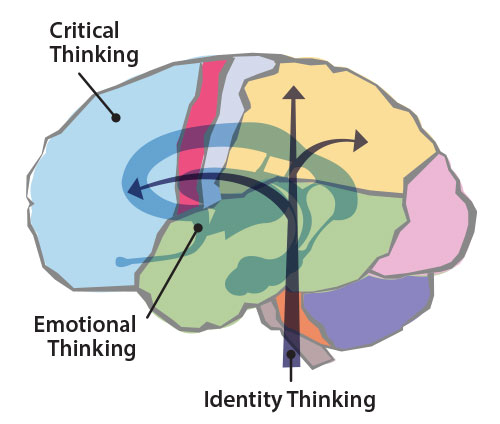

Emotional thinking results naturally from the structure of our brains. Stimulus from the body rises up the spinal chord to pass through the brain stem (the center of consciousness and identity), spreads through the limbic system (the structures that produce emotion), and then propagates through the cerebral cortex. In other words, your brain first asks, "What does this mean to me?" and "How do I feel about this?" before it asks "What do I think about this?"

To manage emotional thinking, ask yourself four questions:

What emotion am I feeling? Excitement, dread, frustration, desire—naming it helps you manage it.

Why am I feeling it? If you can understand the reasons for the emotion, you can effectively manage it.

Is it appropriate to the situation? Is it an overreaction? Is it an underreaction?

What will I do with this emotion? You have a number of options:

Express the emotion but set it aside to think critically.

Modulate the emotion to better match the situation.

Use the emotion constructively to engage the task.

Allow your emotion to connect you with others.

Overcoming "Groupthink"

Groupthink is poor decision making that results when conformity is valued above critical thinking. When dissent is discouraged and everyone is expected to set aside their own perspectives and agree, the group is likely to choose poorly.

Irving Janis articulated this concept in 1972, demonstrating how President Kennedy and his advisers approved the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba because of a lack of diverse perspectives. Later, Kennedy and his advisers overcame groupthink to successfully resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Groupthink

Groupthink happens for a number of reasons:

The group is not diverse, representing just one perspective, with one set of solutions.

Group members are ill informed and unwilling to do the research to become well informed.

Everyone shares the same fundamental assumptions, and those assumptions go unchallenged.

The group members have an unstated goal (such as simple survival) that runs counter to solving problems.

The group is risk-averse and conflict-averse, valuing cohesion above thinking.

The person in charge does not welcome diverse perspectives, driving them out to leave only “yes people.”

Overcoming groupthink is tricky. You start by identifying the cause, checking your situation against the scenarios above.

If the group lacks diversity, you can invite perspectives from outsiders involved in the situation.

If the group members are ill informed, you can conduct research to help the group decide.

You can identify and question fundamental assumptions or unstated goals.

You can challenge the group to allow disagreements for the sake of critical thinking.

Of course, the most difficult situation is when the person in charge does not welcome diverse perspectives. You'll have to decide whether to provide your point of view (at risk of getting marginalized) or to simply go along (at risk of contributing to bad decisions).